Brick: Brick Basics

Brick is a type of clay masonry dating back thousands of years. Brick masonry walls are made of small baked clay units, usually heated in a kiln, laid in mortar, and built up in layers by a skilled craftsman. The size of the individual units may vary, but they are generally proportioned as a rectangular “prism” such that the mason can easily hold his trowel for mortar in one hand and a single brick in the other. The units can vary in strength, durability, they can be solid or hollow, and can have any number of colors and surface finishes. Brick masonry walls can be either load bearing or non-load bearing and can be reinforced or unreinforced.

Making observations about the age of construction, the quality of the brick and mortar, and noting the bonding pattern of the brick will offer some really big clues about how a wall was constructed. The presence or absence of headers being the most significant and valuable information you can look for right away. With the many differences in materials and methods of construction, any project containing historic brickwork will require thorough understanding of the materials of construction as well as the science of building envelopes. Here is a brief introduction to some brick basics.

Brick

Manufacturing of Brick

Bricks are made by heating mineral clays to produce a hard weather resistant material for use in building construction. This is done in a large oven called a kiln. The firing process transforms the clay by fusing together the clay particles into a ‘glass-like’ mass. This process is what differentiates brick masonry from natural stone or concrete masonry.

Depending on the temperature used in firing, the size of the kiln, the source of the clay particles and many other possible environmental considerations, there is considerable variation of brick quality, texture and color throughout the history of brick production and even from batch to batch. Brick manufacturers have learned to control quality and improve the brick properties by blending brick clays with other materials such as silica to reduce plasticity, absorptivity and shrinkage. They would also use other minerals to produce a wide range of finish, texture and color choices.

Historic brick, often produced in smaller, wood fired kilns, possessed considerable variation even within a single firing. In general, historic brick would have three distinct and often visible zones of hardness in their cross-section: the softer ‘inner-core’, a harder ‘transition zone’ and the exterior surface commonly called the ‘fireskin’.

Face brick

Generally the most durable bricks fired in the kiln, are resistant against severe weathering and are used at the exposed portion of the wall. Face brick generally has a minimum compressive strength of 2500 psi and a durable pore structure.

Common brick

Lower quality brick and sometimes brick pieces used to build up portions of walls that are eventually covered with either facebrick or other wall finishes. Common brick generally has a minimum compressive strength of 1250 psi and may be less durable than face brick.

Clinker bricks

A specific kind of historic brick produced when wet bricks are placed too close to the fire in a traditional kiln and became partially vitrified and misshapen. Typically discarded by brick manufacturers, they became popular by some designers for their distinctive architectural detailing. They are considerably denser and heavier than regular bricks, extremely durable, and have minimal water intake. The name is said to come from the sound they make when banged together.

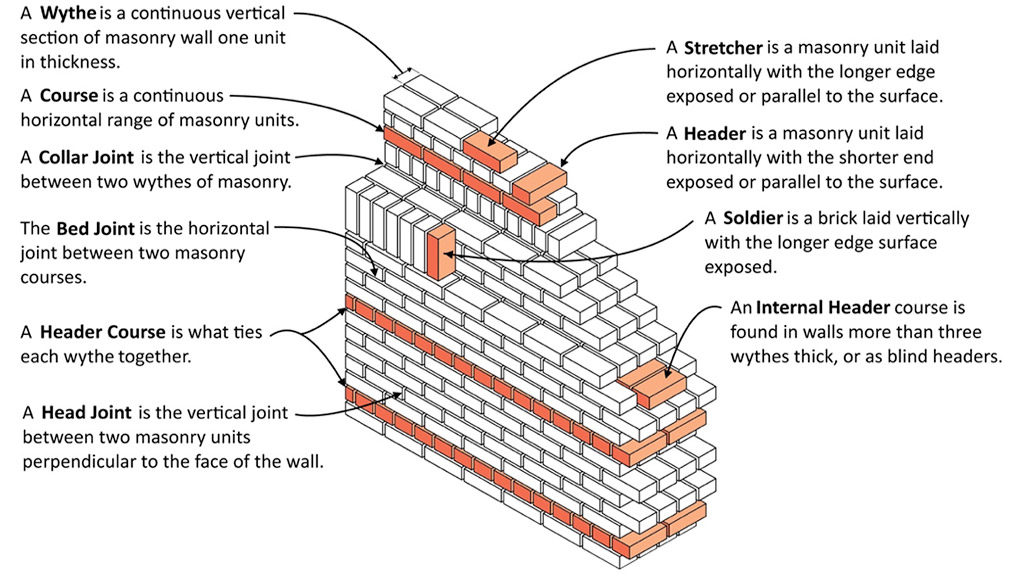

Figure 1: Masonry Terminology

Brick Masonry Construction

Solid Masonry Walls

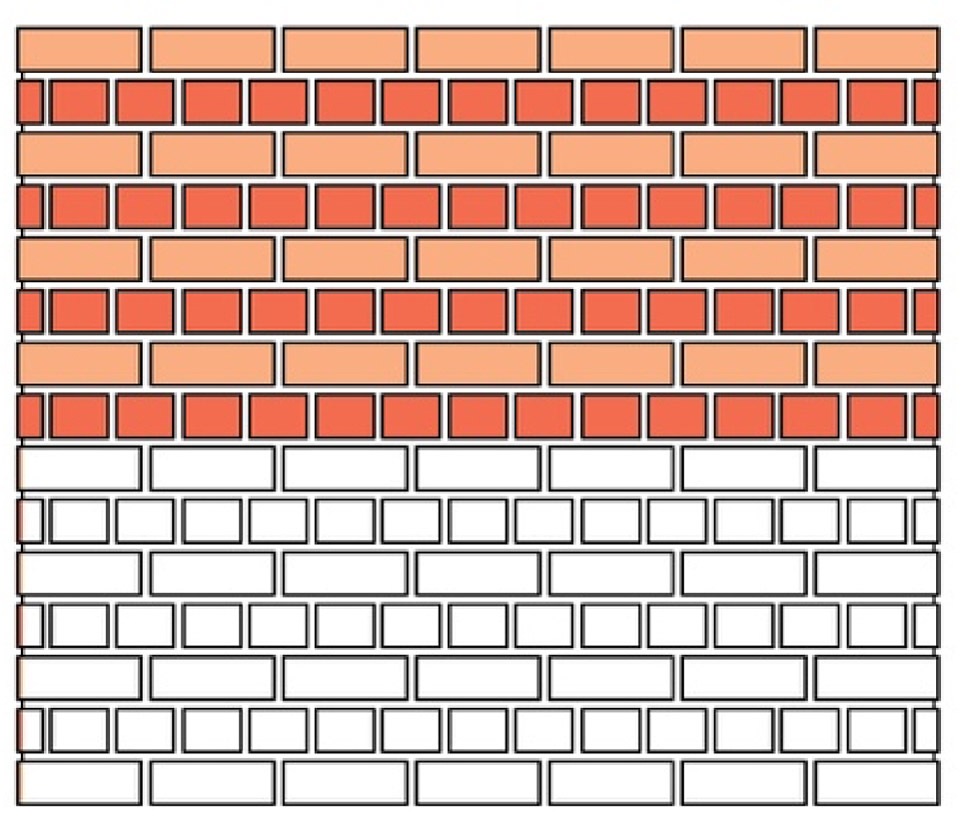

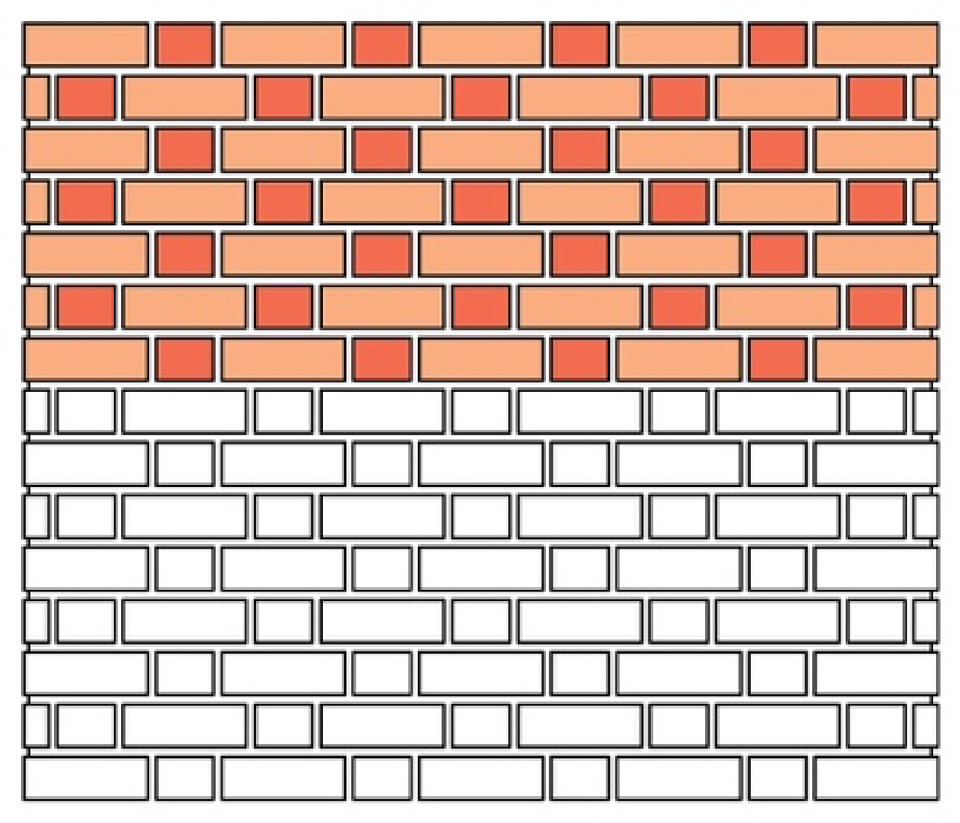

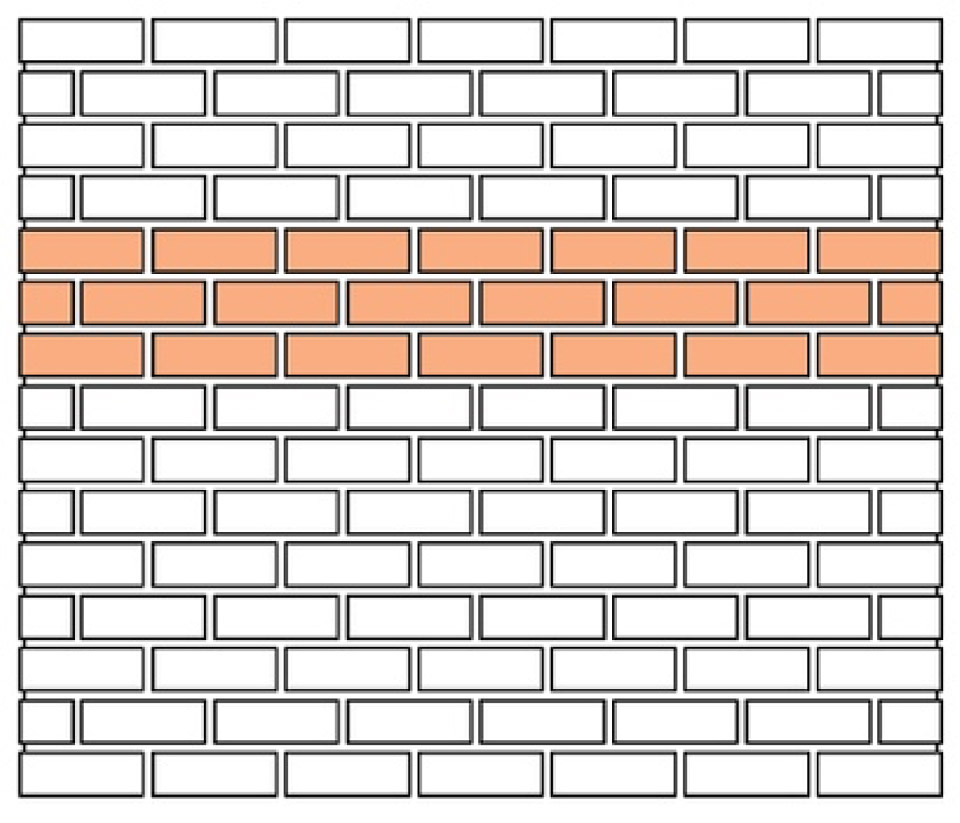

Historic masonry walls are most commonly constructed out of multiple layers of brick. The horizontal rows of bricks are referred to as courses, and each unit layer of thickness is called a wythe. The brick units are then stacked and bonded together with mortar in specific patterns, or “bonds”. Bricks that are laid parallel to the length of the wall are commonly referred to as “stretchers” and those units laid perpendicular to the length of the wall are called “headers.” In typical masonry wall construction, the headers laid across two wythes of brick are what tie the wall together (see Figure 1).

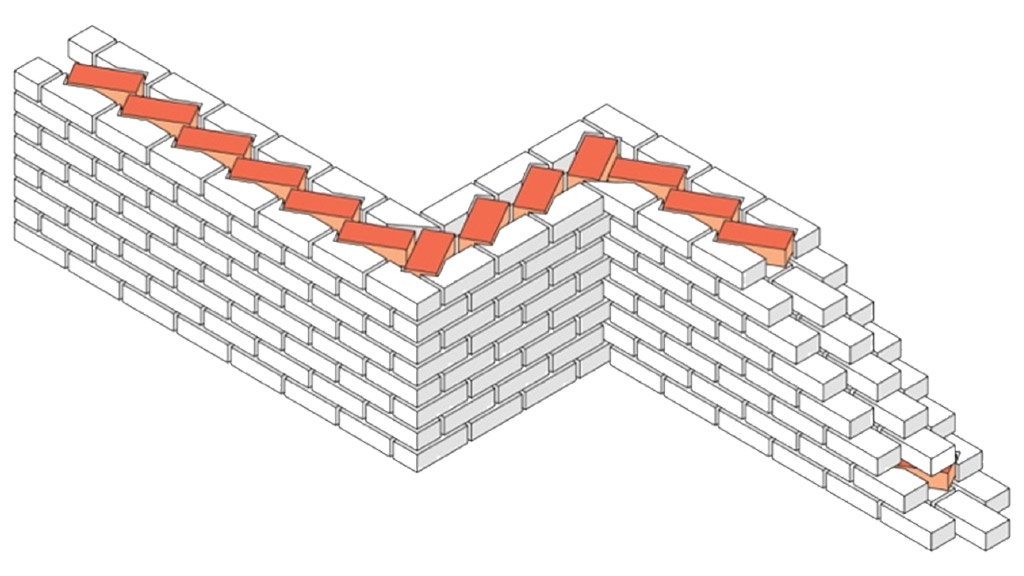

Figure 2: Blind Header or Clipped Bond Wall Construction

Brick Bonding

The outermost surface of a brick masonry wall is generally laid out in a defined pattern referred to as the ‘brick bond’. This pattern is not only an architectural feature of the building, but is also expressive of the wall’s structure configuration. Headers and stretchers are laid out such that they can create patterns from the simple to the very complex and intricate depending on what the architect/builder chooses. Below are some of the more common brick bond patterns.

| Table 1: Masonry Bonding |

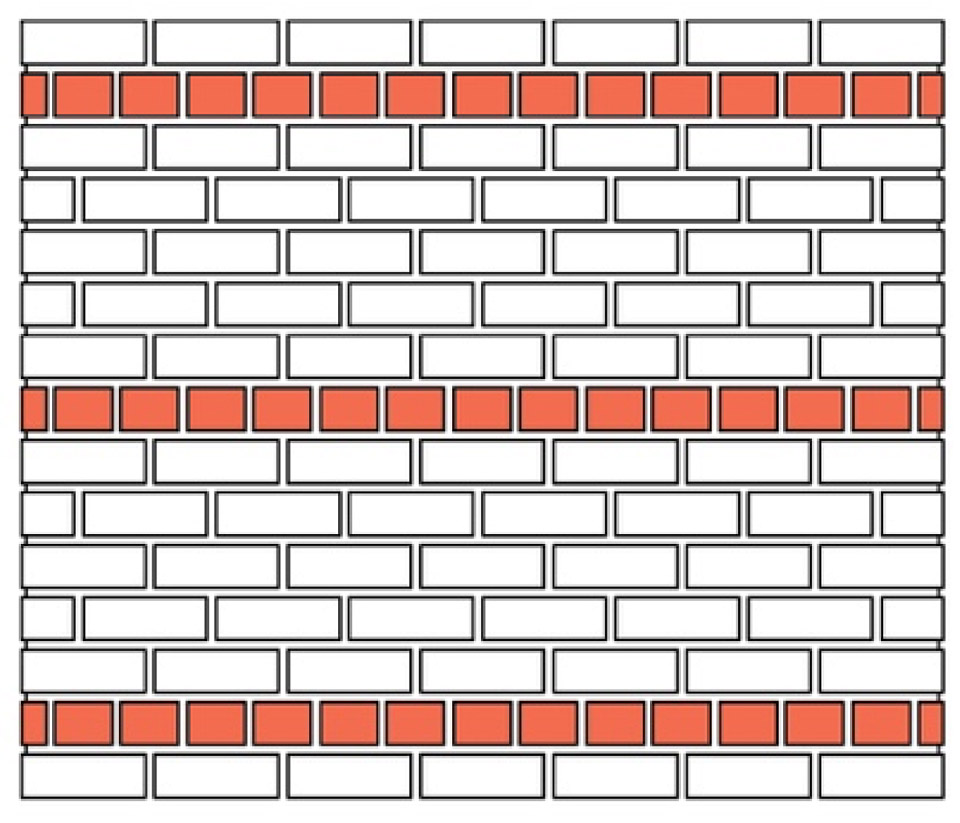

Common Bond | Common Bond has a course of headers between every five or six courses of stretchers (or 7 or 8 or 9 in the west!). This is also known as American Bond, and is the most common brick bond used in solid masonry bearing walls in the United States. |

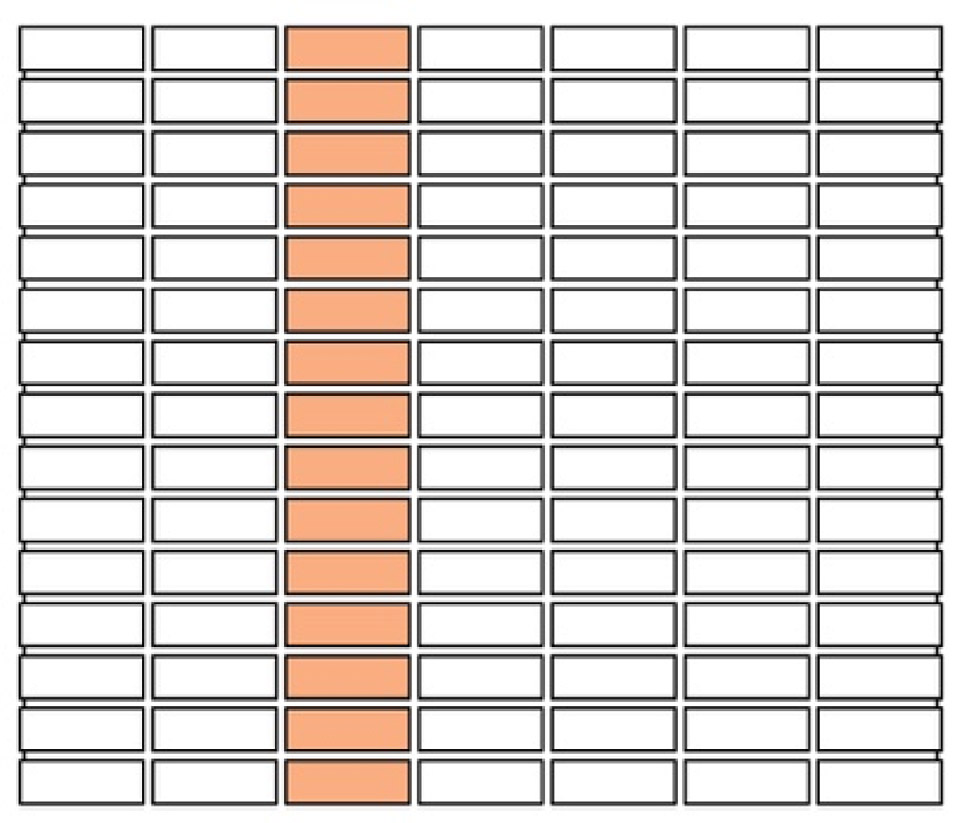

Stack Bond | Stack Bond has successive courses of stretchers with all head joints aligned vertically. Common in the 1970’s, this bond requires horizontal joint reinforcement and wall ties in unreinforced wall construction because the units do not overlap. |

English Bond | English Bond is a modification of the common bond that has alternate courses of headers and stretchers in which the headers are centered on the stretchers and joints between the stretchers line up vertically in all courses. |

FLemish Bond | Flemish Bond has alternating headers and stretchers in each course, each header being centered above and below a stretcher. Flash headers with darker ends are often exposed in patterned brickwork. Many modifications to the Flemish Bond can be found to enhance the visible architectural pattern. These include the Flemish Cross Bond, the Flemish Diagonal Bond and the Flemish Garden Bond.C |

Running Bond | Running Bond, which is commonly used for cavity and veneer walls in new construction, is composed of overlapping stretchers. Because there are no visible headers present, it is likely that metal ties are present. This bond is rarely seen in historic construction, but was sometimes desired for architectural purposes. In these rare cases, Blind Headers or Clipped Bond construction was used (see Figure 2). |