Joints: Expansion Joints

Figure 1. Close-up view of an expansion joint location in clay brick under construction. Backer rod material is being used to prevent mortar clogs in the expansion joint (from BIA Technical Note 18A, Photo 1).

Any discussion of expansion joints should probably begin with correctly defining the term. Expansion joints in masonry are basically flexible, compressible joints that allow the surrounding masonry to expand without damaging itself or adjacent materials. The most common application for expansion joints is within clay brick masonry because clay brick expands irreversibly over time. On the other hand, concrete block and other cementitious products shrink over time and require joints to control cracking, known as “control joints”, which will be addressed in a separate article.

It should be noted that there are other masonry products that can expand and, therefore, require expansion joints. For example, most natural stone masonry expands slightly when wet and when heated (for example in direct sunlight). If you encounter a project with large expanses of natural stone without any expansion joints, you might consider raising a red flag with an RFI or other written correspondence.

Because expansion joints are intended to accommodate expansion, their most important attribute is compressibility. If an expansion joint cannot be squeezed together (throughout the masonry thickness), it simply is not doing its job. One of the most common types of failure in expansion joints occurs when the joint is not kept clear of mortar. Often, this can result in cracking and spalling of the brick in the vicinity of the mortar blockage. In order to prevent this, consider using backer rod or other compressible material throughout the masonry thickness as masonry is placed (not just at the exterior surface), as shown in Figure 1. If the joint is already full of a compressible material, there is no way for it to become clogged with mortar.

According to the Building Code, specifying the location of expansion joints is the responsibility of the Designer (usually the Architect), and this design should include specific locations for each joint, not merely a single note. If you, as a mason or contractor, are tasked with performing this aspect of the building design, a written complaint about this abdication of responsibility should be sent to the Owner and kept in your project file. If you cannot avoid taking on this design task, protect yourself by using standard industry practice guides, such as BIA Technical Note 18A. Basically, this document recommends joint spacing of no more than 25 feet and no more than 10 feet from building corners.

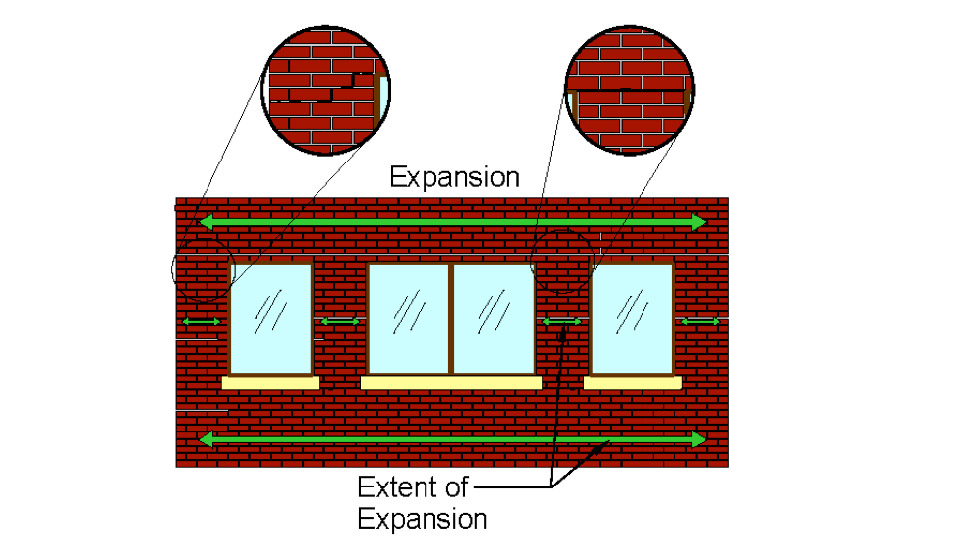

Figure 2. From BIA Technical Note 18A (Figure 5), schematic elevation view of clay brick wall showing crack patterns that can form around window openings without expansion joints.

In addition to appropriate spacing, it is beneficial to locate expansion joints within a wall elevation at locations where expansion-related cracking would be most likely to occur. For example, uneven expansion around window and door openings can create stress concentrations and cracking that can be avoided by placing expansion joints at the corners of these openings (Figure 2). Similarly, expansion joints at changes in wall height or geometry can be especially effective.

Figure 3. View of brick veneer on high-rise building that has cracked and bowed due to missing expansion joints beneath shelf angles.

Another common expansion joint problem is improper or missing horizontal expansion joints (i.e. joints that accommodate vertical expansion). Clay brick and other masonry materials generally expand volumetrically, meaning they grow horizontally, vertically, and even through the wall thickness (although this direction is typically negligible). The most common need for horizontal expansion joints is beneath shelf angles or other intermediate supports in a multi-story building. Clay brick masonry veneer in this application tends to expand vertically over time and can be restrained by the shelf angle and building frame, which is not expanding and, in fact, generally shortens somewhat over time. If a compressible expansion joint of sufficient width is not provided between the top of the brick and the bottom of the shelf angle, the restrained expansion of the brick can cause bowing, cracking, and even collapse of the veneer (Figure 3).

Figure 4. View of lipped brick installation at shelf angle without functional expansion joint (only fillet sealant joint).

Architects and owners often dislike the appearance of horizontal expansion joints in masonry, and they sometimes will minimize these joints to such an extent that they are no longer functional (Figure 4). If you are faced with this situation, consider other measures to minimize the appearance of the joint, while maintaining its functionality. For example, try to find a good bed joint mortar color match for the expansion joint sealant. There are some textured sealants available off the shelf that may also improve appearance, or you can even brush crushed mortar into the sealant surface to remove the glossy sheen of the joint.

Remember that unless expansion joints are compressible, they cannot do their job.