Anchors, Connectors, and Fasteners: Post-Installed Anchors in Masonry

Words: Margaret Foster

Figure 1. Photograph from the Accident Report by the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board Ceiling Collapse in the Interstate 90 Connector Tunnel, Boston, Massachusetts, July 10, 2006.

The field of post-installed anchors has become increasingly complex over the past decade. There is a new set of qualifications for anchors published by ACI: 355.4 Qualification of Post-Installed Adhesive Anchors in Concrete. There are numerous new calculations, certifications, and tests related to installation in various configurations and conditions of heat, overhead applications, cracking, and load cycling. Where do anchors in masonry fall in this increasingly complex landscape?

For better or for worse, most of the recent developments in post-installed anchors do not currently apply to installations in masonry. For example, ACI 355.4 applies only to anchors installed into a concrete substrate, and it is not applicable to anchors in masonry (even concrete masonry). Many of the recent changes in the post-installed anchor industry stem from a few failures of adhesive (epoxy and acrylic) anchors due to a phenomenon called creep rupture. The most prominent of these failures in the United States occurred on July 10, 2006 when a concrete ceiling panel fell inside Boston's Fort Point Channel Tunnel (part of the “Big Dig” project), killing a passenger and injuring a driver (Figure 1). There were several contributing factors that led to this collapse that included poor installation and hole cleaning. However, the tragedy also brought to light the susceptibility of polymer-based adhesives to creep rupture, a mechanism wherein an adhesive in constant direct tension stretches over time until it fails. Many of the recent changes in the industry are a direct result of this incident, including certifications for overhead installations (in concrete) and the calculations described in ACI 355.4 that are intended (in part) to protect against creep rupture failure of adhesive anchors.

These concerns are less common in masonry for several reasons. First, many anchors in masonry are cast into grout during construction or grouted into place following construction. Cementitious grouts used in masonry construction are not susceptible to creep rupture, nor do cementitious grouts soften in high-temperature conditions. Additionally, the most common direct tensile anchor applications are hangers (although there are others), and it is relatively rare for masonry to be used in floor and ceiling applications in modern construction.

Figure 3. View of a shear test of an anchor in clay brick masonry using a spreader bar to avoid confinement of the test anchor.

Testing

Most often, engineers use manufacturer’s tables to design anchors in masonry. The Code (TMS 402) also allows designers to conduct tests (a minimum of five) to determine the load capacity of anchors in masonry. Proper testing of anchors should not “confine” the masonry being tested, which typically means that the reactions of the test apparatus should be twice the anchor embedment away from the anchor being tested (Figure 3). Be careful with manufacturer’s representatives who claim to offer quick and cheap testing of anchors with small devices. These are usually not appropriate for tests in masonry.

Figure 4. View of an empty screen tube of the type used for adhesive anchors in masonry.

Installation

Post-installed anchors in masonry are subject to many of the same potential installation errors as post-installed anchors in other substrates along with some unique conditions. One of the most common installation concerns for adhesive anchors in masonry is proper cleaning of anchor holes. Dust or moisture in an anchor hole can dramatically decrease adhesive anchor capacity. Another common installation concern is voids and incomplete filling of anchor holes with adhesive. It is generally better to protect the surface if necessary and allow some adhesive to squeeze out of the hole than to try to partially fill the hole to avoid adhesive coming to the surface.

One of the fairly unique aspects of installing anchors in masonry is that the substrate into which anchors are being installed is often not solid. Ungrouted concrete block, open brick collar joints, and rubble stone voids can all allow adhesives to drain into the masonry and away from the anchors they are meant to adhere. Except for solidly grouted concrete masonry, adhesive anchors in masonry should generally be installed into screen tubes using relatively viscous adhesives that are approved for use with screen tube installation. Screen tubes keep adhesives from draining into masonry voids while allowing enough adhesive to squeeze through the screen to create bond with the masonry (Figure 4). Screen tubes should be filled completely with adhesive then placed into a tightly-fitted hole, and the anchor should then be pushed into the adhesive-filled screen tube, displacing adhesive into contact with the substrate.

Figure 5. View of a helical anchor being installed into a clay brick masonry wall.

In addition to adhesive anchors, other types of masonry anchors should be installed with careful attention to manufacturer’s instructions. For example, helical anchors (Figure 5) must have pre-drilled pilot holes of exactly the correct diameter to work properly.

Figure 6. View of a socked anchor in clay brick masonry after completion of a tensile test. The brick surface is spalled away, making the sock beyond more visible.

Socked anchors containing cementitious grout are an excellent option for larger and longer anchors in masonry (Figure 6). Similar to screen tube anchors, the socks allow some of the adhesive material to seep into contact with the masonry. However, the socks also expand and conform to the surrounding surfaces, creating a strong mechanical interlock with most masonry substrates. Socked anchors should be fabricated with appropriate sock fabric and grout materials. Specialized pumps and equipment may be required for the sock injection.

The use of expansion anchors in masonry substrates should also be executed carefully. In older, softer masonry, expansion anchors can sometimes cause spalling failure of the masonry surface. It may be prudent to install sample anchors in a discreet location in order to establish an appropriate installation torque.

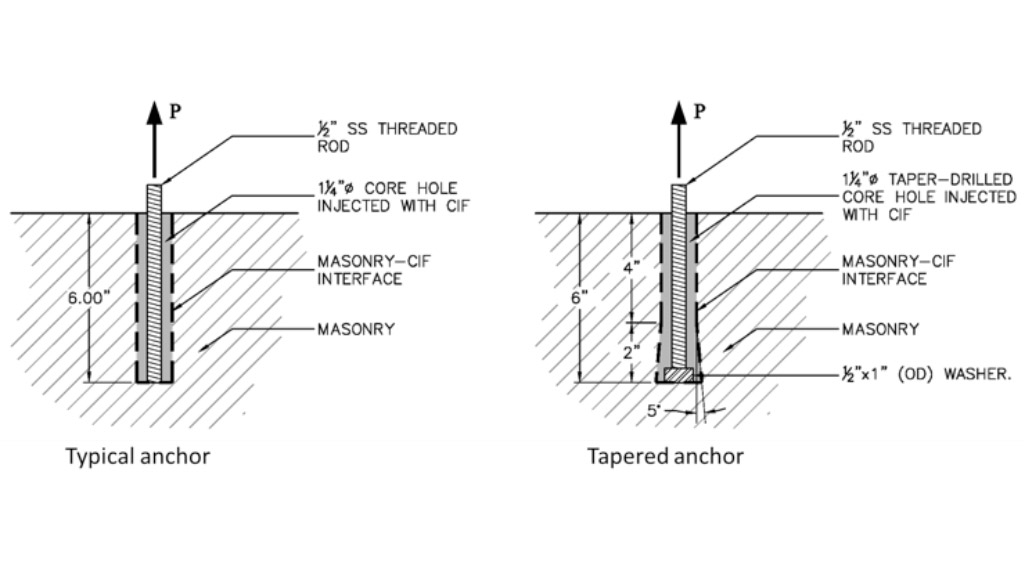

Figure 7. Diagrams of a typical grouted anchor (left) and a reverse-tapered anchor (right).

Developments

The field of post-installed anchors is constantly changing, with new adhesives, new anchor geometries, and new accessories appearing all the time. The use of reverse-tapered anchor holes in masonry is emerging as a new option to increase capacity or decrease embedment length (Figure 7). Other new The field of post-installed anchors is constantly changing, with new adhesives, new anchor geometries, and new accessories appearing all the time. The use of reverse-tapered anchor holes in masonry is emerging as a new option to increase capacity or decrease embedment length (Figure 7). Other new anchor materials and methods will certainly follow. All of them will likely require masons and installers to very carefully ... “follow manufacturer’s installation instructions.”